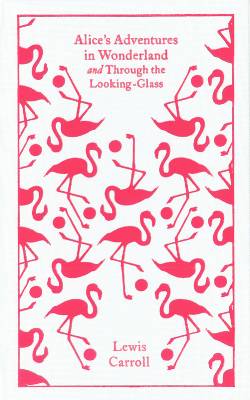

I would venture to say that there are at least one hundred

different editions of Alice’s Adventures

in Wonderland, and probably more. I am looking at three different editions

of the novel in this blog, but I chose just one—my favorite—for the book

description.

Book description: 2010. Format: Hardcover. Trimsize: 5 3/4" x 8 1/4". Pages: 160. Smooth, cloth-like binding

with metallic pink stamping on front cover and spine. Fourth printing. Full

color dust jacket and full color illustrations throughout by Camille RoseGarcia (1970- ), an internationally known artist whose work has been in

magazines such as Rolling Stone, Juxtapoz,

and Modern Painter. Semi-glossy

paper used to showcase Garcia’s illustrations. Black endpapers with a pattern of small lavender illustrations. Published

by Collins Design, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers. Text first published

in 1866 and written by Charles Lutwidge Dodson (1832-1898), better known as

Lewis Carroll, who wrote a sequel to Alice’s

Adventures in Wonderland called Throughthe Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There in 1871. Book is in excellent

condition; only one previous owner. Book designed by Agniszka Stachowicz.

Printed in the United States of America. No markings, bookplates, or other

notes inside covers or on pages. Printed using offset lithography and commercially

bound. No headband is present, not even a decorative one.